Before COVID, the MPL industry was moving into a period of firmer pricing. This firming was driven by a deterioration in operating results due to a decade of soft pricing coupled with rising claim severity, driven in part by nuclear verdicts. However, once COVID-19 struck—the official World Health Organization Pandemic declaration came on March 11, 2020—all bets were off. The Trump Administration declared a nationwide state of emergency just a few days later, and states began to implement shutdowns affecting schools, businesses, non-essential travel, and more.

For the MPL industry, shutdowns affected the courts in virtually all jurisdictions. Court activity was severely restricted in many jurisdictions, halting jury trials, although the length of court closures varied significantly by jurisdiction. That put at least a temporary hold on claim settlement activity, though the length of the hold was quite variable, depending on government policies in different jurisdictions. In 2020, 34 states suspended in-person proceedings statewide, while 16 states suspended those proceedings on the local level. In addition to suspending in-person proceedings, many state and federal courts restricted or ended jury trials, granted extensions for court deadlines, and encouraged or required teleconferences and videoconferences in lieu of in-person hearings.

In addition, the unprecedented environment left plaintiff and defense attorneys and their clients without any guide to settlement discussions, dampening settlement activity. These issues bring up two important questions and another related question:

- How are actuaries accounting for the slowdown, i.e., what actuarial methods are they using?

- Should the methods differ for occurrence vs. claims-made reserves?

- If rumors are true that plaintiff attorneys faced with staff shortages are focusing attention on claims above $3 million, how should that be handled in terms of reserves?

Actuarial Methods. “This pre-COVID period is far and away the one that I’m the most concerned about,” said Mosler. “I feel like the industry as a whole is reserving pretty optimistically for these periods.” He identifies two separate issues in terms of accounting for slowdowns and specific actuarial methods to be used in these cases. The first issue is a slowdown in the rate of claims being paid; the second is whether there is a slowdown in establishing reserves on open claims.

Traditional actuarial methods that rely exclusively on payments have been significantly impacted by slowdowns in the courts. Methods that rely on payments and case reserves are expected to be more accurate. “If it’s possible to conclude that there isn’t a slowdown in establishing case reserves, then it is possible to rely on reported losses (paid plus case reserves) in the traditional loss development method rather than paid losses alone,” he continued. “This is a pretty common approach in MPL both before and after the pandemic because there is information in those case reserves that actuaries can rely on.”

Paid data can still be used, but with adjustments. The Berquist-Sherman method very directly adjusts for slowdowns in payments, Mosler noted. The method relies on restating history to a consistent rate of closure that is appropriate for this situation.

Mosler utilizes this method on indemnity and defense costs separately because in many cases, while indemnity payments have slowed dramatically, defense payments have not. “Putting them together can result in too much of a slowdown,” he added, “so it’s more accurate to look at the components separately rather than combining them.”

From Milford’s perspective, there is no easy answer to the question of how to account for the slowdown. “While slower resolution was observed in many jurisdictions, it was not observed in all,” she noted. “And even in jurisdictions where there were clearly some slower settlement patterns, the slowdown was often not consistent across all report years.

“This inconsistency by year makes it difficult to rely on broad-brush actuarial adjustment processes typically used to adjust data to a consistent settlement level,” she continued. “Actuaries will need to assess if there is a distortion in the data, and, if there is, what level of distortion is present and how each coverage year might be impacted.”

Specifically, she noted that because of the maturity of these pre-pandemic coverage years, it might make sense to make targeted year-by-year adjustments to development patterns. “Using projections of frequency and severity, based on pre-pandemic levels and trend could be a reasonable option if there is no reason to believe there has been a change in frequency or severity levels. In areas impacted more by social inflation, historical severity levels may be less appropriate for recent years,” Milford added.

For Karls, there is no doubt that the basic actuarial development methods are distorted, so that using these methods without adjustment would result in a biased answer. Therefore, these methods would need to have an adjustment factor built or be given less weight, he said.

“For these reasons, I like the frequency/severity methods,” Karls continued. “The frequencies are relatively known, and the severities are what we’re estimating. I’ve been discounting the severities that we’ve been seeing in 2020 and 2021, and really going back to 2018 and 2019. This sounds pretty basic, but it is a better approach than relying on a development method.”

Karls has seen the defense costs slow, but not nearly to the degree that claim closures slowed down. “Ultimately, the average defense cost is going to be higher because the meter ran while claims didn’t progress,” he added.

Digging deeper into defense costs, Karls said one interesting finding is that deposition costs, on average, are slightly lower than what they were pre-pandemic. Deposition costs are, in fact, the single most costly event for the defense because while trials are more expensive individually, claims don’t go to trial all that often. He attributes the decline to the fact that even after the worst of the pandemic has passed, approximately 20% of all depositions are done virtually, which reduces travel costs. Judges are pressuring defense and plaintiff lawyers to settle because their dockets are so backed up, he noted.

Occurrence vs. Claims-made Reserve Differences. Because the vast majority of MPL business is written on a claims-made basis, the issue for this business boils down to judgment about what is happening to claim severities, Karls noted. “We know how many claims there are,” he continued. “While there is some uncertainty in terms of what proportion of those claims will involve an indemnity payment and which ones won’t, that proportion tends to be pretty stable.”

What’s hard to pin down is the severity, he said, adding, “From a loss perspective, what the closure of the courts and the lack of trials did was curtail settlements. There is no greater motivation in my mind for a settlement to occur than a pending trial date. We didn’t have any trials for virtually 18 months, which took that very large motivator away. Claims and claims closing both slowed down. In particular, I’m most concerned that large claims slowed down more so than smaller ones. As an industry, I think we might be sitting on a higher proportion of large claims that are about to settle as the courts open back up.”

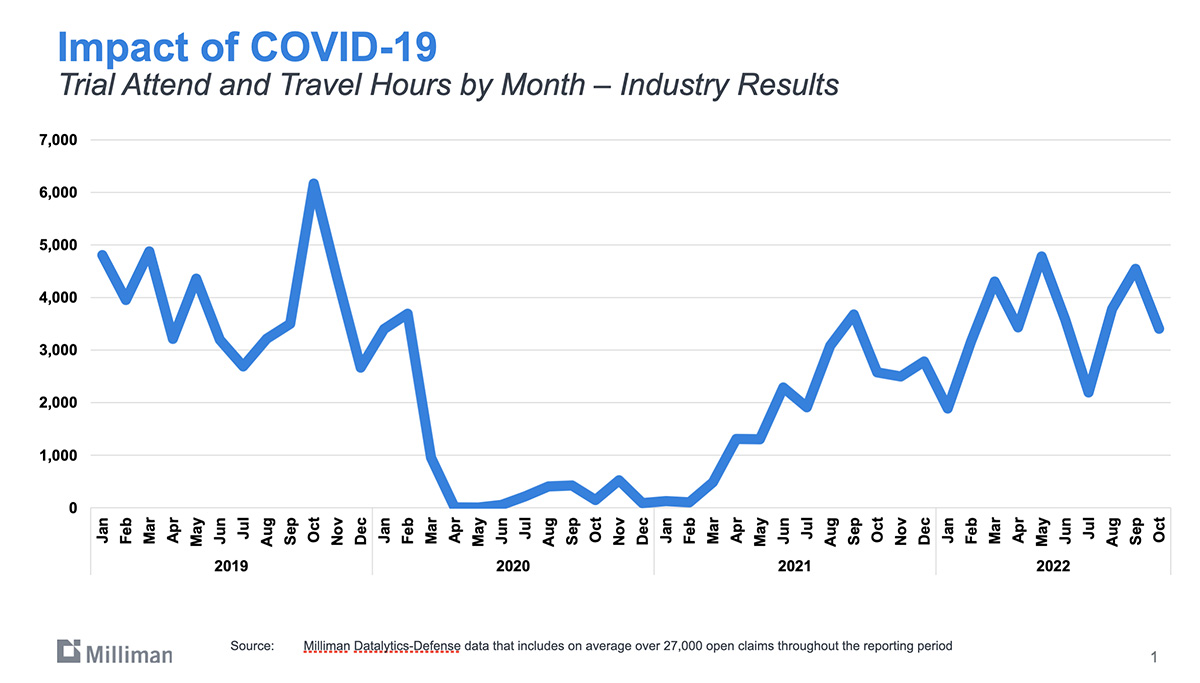

Milliman collected data on the amount of trial hours by month that offers some revealing insights into the revival of claims activity. That data show that claims activities involving the courts is virtually back to where it was pre-pandemic, as seen in Figure 1. What’s not accounted for, however, are the missing 18 months when activity all but halted.

In terms of occurrence versus claims-made reserves, Mosler distinguished between two time lags:

- The time lag that occurs between when an MPL incident is reported and when a claim is made

- The time lag that occurs between the claim being filed and the claim being closed

Essentially, reserves are set up because a claim isn’t paid as soon as it is filed. Occurrence reserves involve both the reporting lag and the settlement lag. “The question then becomes if there is a difference in the reporting lag and whether someone who has had a bad health outcome is actually going to take longer to file a claim,” he said. “In a majority of recent analyses, I haven’t seen evidence of a slowdown in claim reporting. It’s possible that there was one in 2020, but generally indications are that it is caught up by now.”

In the final analysis, Mosler noted that in most cases the same adjustment can be made for claims made as for occurrence.

Milford noted that in relation to settlement activity, the process for assessing the level of distortion related to the pandemic slowdown would be similar for claims-made and occurrence coverage forms. “However, for business written on an occurrence basis there are added uncertainties regarding how frequency will develop given the period of reduced patient contact during the pandemic-related shutdowns as well as the future uncertainty with respect to the impact of that period of reduced contact on patient acuity,” she said.

“Anecdotally, thus far there has not been a material impact on post-2020 frequency related to delayed care associated with the shutdowns and potentially extending longer than mandated shutdowns due to fears regarding returning to normal in-person interactions,” she added.

Plaintiff’s Attorneys Aim Higher. The US labor shortage is a well-known trend that is affecting many industries. Economists cite COVID-related phenomena (early retirements, deaths, illnesses, fears, childcare shortages, reduced immigration, etc.) as reasons behind this trend, which doesn’t look to abate any time soon. There’s speculation that a shortage of plaintiffs’ attorneys has motivated the plaintiffs’ bar to focus their attention on claims of $3 million and higher, up from $1 million. If it is indeed true that the plaintiffs’ bar is shifting their focus to higher claims, this too could impact claims reserving.

While Milford hasn’t heard about rumors consistent with this narrative, she is cognizant of the tendency for the plaintiff’s bar to focus on higher-revenue claims. “My sense is that re-focus was more attributed to the higher relative cost to bring these types of claims,” she said.

Like Milford, Mosler hadn’t heard about this alleged plaintiff attorney staff shortage, but he believes it makes sense. “Actuaries, attorneys, accountants, and IT are four areas where there is a lot of turnover, and where there’s a lot of potential for remote work,” he continued. “Lots of professionals are quitting and finding jobs that are more convenient, and it can cause issues.”

“Considering the idea of a $3 million claim limit, I think this will initially seem like a good thing for physicians. The last thing a physician wants is to have their personal assets at risk in a lawsuit. A higher limit gives greater protection. But, it’s important to also consider that the higher limit could make a lawsuit more likely and lead to a higher premium than there was at the $1 million limit that many physicians have currently,” he said. “For the hospital that insures physicians, they have the same concern about the higher cost. The difference is that the higher limit may not give them any additional protection as many hospitals have a high self-insurance retention.”

Mosler noted that if this trend turns out to be due to a capacity shortage that is eventually resolved, the affected years will negatively affect trend lines and make it more difficult for actuaries to project the future in terms of whether there will be fewer high-value claims going forward or not.

Karls agrees with the premise that plaintiff’s attorneys have gotten more particular over time in terms of the types of cases they bring for all sorts of reasons. “I do believe that plaintiff’s attorneys are very good underwriters of claims in that they know what cases to bring and what cases not to bring.”