In a fast-paced world filled with numbers and data, technology is an essential requirement for all business operations. Like many others, the insurance sector is poised for technological transformation. This change requires managers who not only effectively handle tasks, timelines, and resources, but who are also proficient at human factor management.

The people who make up organizations possess basic needs that are often overlooked. That’s why it is imperative to take a step back and understand why people behave the way they do. This is particularly consequential in environments with compressed timelines, where people experience the pressure to deliver a new technology product quickly.

This article is the first part of a four-part series about the people behind new technology implementations.

This article explores intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, how to avoid traps such as groupthink and social loafing, and how to provide the essentials necessary to establish the project dream team. In subsequent articles, we will explore project decision-making, prioritization, burnout, and communication.

Human Needs and Intrinsic Motivation

To understand how to successfully implement a technology project, it’s important to understand some basic facts about human motivation. You can see that when your team is motivated, they can accomplish project implementation successfully, but when they aren’t, implementation will be a long and difficult grind. There are two types of motivation according to American psychologist Abraham Maslow: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.1

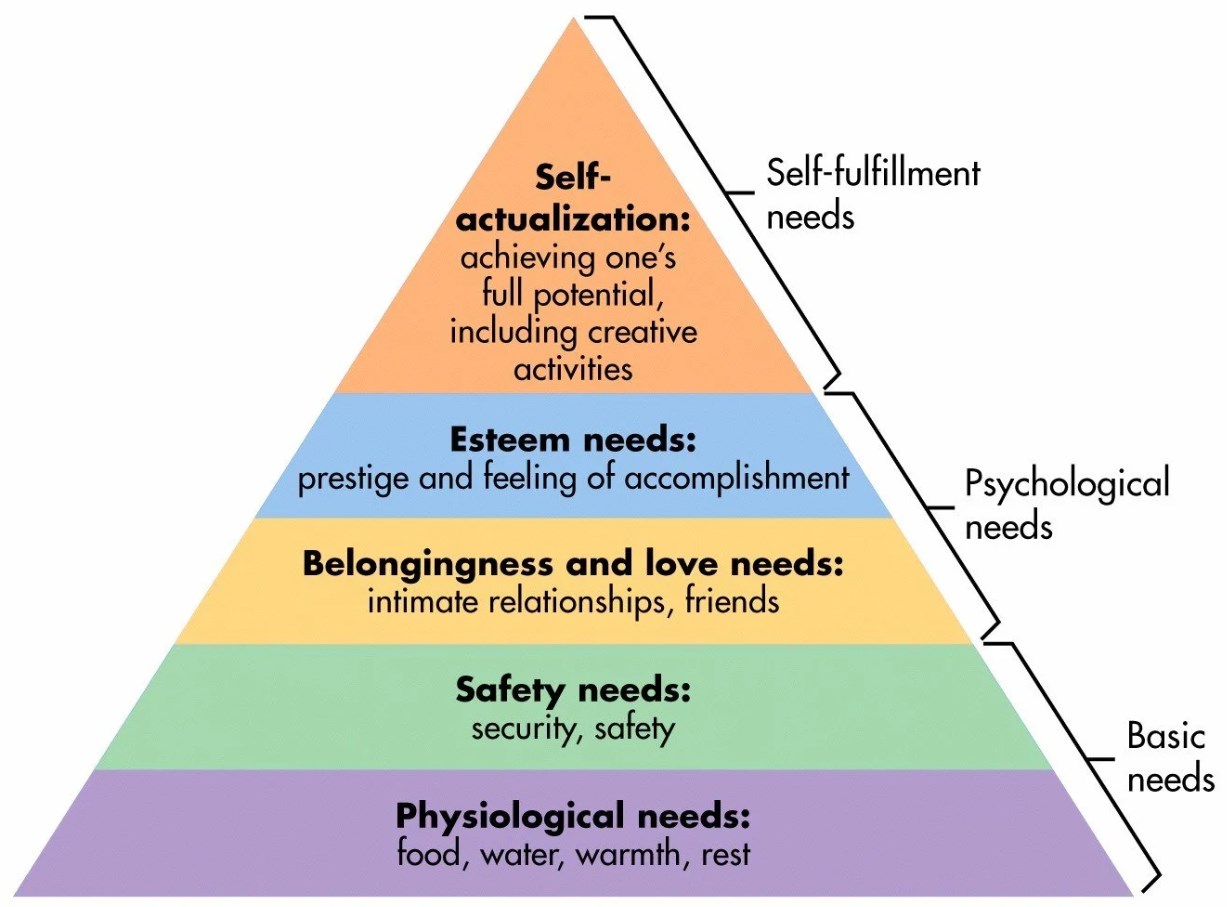

As seen in Figure 1, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs outlines the typical order in which people require their needs be met—the first being the most basic, which are physiological, and the last being self-actualization. To understand why your team members act the way they do during project implementation, you must bear this hierarchy in mind.

Figure 1. Source: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs2

Intrinsic motivation comes entirely from within and is integrated into an individual’s identity. It is therefore a powerful and continuous source of motivation. In contrast, extrinsic motivation drives individual performance for reasons other than for enjoyment, such as to receive a tangible reward or avoid punishment. Progressing up the pyramid involves increasingly higher levels of intrinsic motivation.3

Why is this important to project management? Because motivation is a critical factor in successful technology implementations—if you can get this part right, the actual technology pieces will come much more easily. While the implementation of new technology can bring excitement, there may also be fears around whether the new technology will replace the jobs of the implementation team or others in the organization.

This perceived threat can undermine an individual team member’s need for safety, which is a basic need in the Maslow Hierarchy. You can counter this fear by reminding your team of the goal of whatever your specific technology implementation project is. Generally, when replacing legacy tech with newer tech, efficiency gains will enable your team members to accomplish routine tasks more quickly while eliminating manual tasks. They will then be able to spend more of their time on higher value-add tasks, such as helping customers. These tasks are located higher up on Maslow’s Hierarchy, helping them meet their needs for esteem and self-fulfillment, which are intrinsic motivations.

Increased intrinsic motivation can further be encouraged via an environment that promotes autonomy, relatedness, and competence.4 Autonomy is the belief that an individual has choices and has a say in their work responsibilities. This is important to understand, because you must motivate the individuals before motivating the team as a whole. Team members should be allowed to choose to perform rather than being pressured to deliver.

This is not to say that deadlines are not important, but creating a space where employees feel comfortable communicating when they are overwhelmed and may not reach or need help reaching their deadlines is vital. This can be done with actions as simple as tone of voice or a verbal conversation as opposed to a written message.

Relatedness targets the motivations of love and belongingness as well as self-actualization by deepening connections with others. You may want to identify how team members feel regarding what they do, encourage them to develop their values while working, and connect their work to a higher cause. That cause could be moral, spiritual, political, corporate, and so on.

If a team member excels at, or even enjoys, a particular task such as testing code, documenting how to do something, or presenting project results to the team, you could then assign them these tasks when available. Competence is an aspect of self-actualization that is realized when team members have the right skills and the opportunities to showcase these skills.5

Instead of setting result-oriented goals, you can facilitate higher levels of motivation by making resources available for learning and setting learning goals. If a team member expresses a desire to be a team leader or project manager, you could help them progress towards this goal by providing training as well as the opportunity to shadow a high performing project manager instead of associating that wish with completing “x” amount of tasks in “y” amount of time.

Extrinsic Motivation

Most workplace motivators are outdated and dependent upon short-lived extrinsic motivators. According to psychologist Victor Vroom, these short-lived motivators must rely on three elements to be successful:6

- Expectancy: The belief that putting forth more effort will lead to better performance

- Instrumentality: The belief that better performance will be acknowledged with a reward

- Valence: The desire to gain whatever reward was promised

If an employee has continuously and steadily increased the amount of time they work, they may anticipate acknowledgement with overtime pay or a higher end-of-the-year bonus if this has been the result in the past. Extrinsic motivators usually motivate team members in the short-term but have not been proven to be effective long-term and may sometimes backfire.

That’s because extrinsic motivation can fall victim to the “overjustification or over-reward effect,” which shows that excessive or unjustified external rewards can reduce intrinsic motivation.7 This is not to say that monetary or other extrinsic motivators should never be considered, but companies and project managers should be cognizant of this fact and potentially pivot to an increase of intrinsic motivators.

Potential Negative Consequences

Don’t dismiss all this as theory that won’t apply to you, your organization, or your team. These are real-world issues that impact technology project implementation. When recognized and included in your plans, they can accelerate the successful completion of your project. When dismissed, they can become self-fulfilling prophecies that wreak havoc on your project.

Here’s what can happen if your project implementation team members’ needs aren’t met: The group may fall victim to groupthink. Groupthink occurs when a team becomes too cohesive or conformist and isolated from outside perspectives. It leads to poor decision-making, reduced creativity, and increased risk of project failure.8 Social loafing is another phenomenon that that can endanger project implementation objectives. This phenomenon can occur when the size of a team increases and leads to a decrease in the effort and motivation of individual team members.9

To avoid groupthink and social loafing, managers should encourage a diversity of skills and opinions among group members, foster dissent, or encourage individuals to challenge the group’s views and assumptions. Almost everyone has been in a meeting where someone strongly disagrees with what is being suggested by the leader or group.

Rather than tamping this view down and discrediting the view outright, it should be given pause and true consideration. It is difficult to do this, especially if personal experience has taught the leader or group otherwise. The group should ask questions and figure out how that idea came about.

Note that some people do not always feel their needs for safety are fully met, so it is essential not to mock ideas or ignore them regardless of whether or not they are credible, helpful, or useful. Encouraging the free flow of ideas can increase the likelihood that more people will participate and offer new ideas. Facilitate communication and accountability by calling on individuals to contribute (individual performance improves with an audience, which is known as social facilitation).10 It’s also important to monitor and review through fair evaluation practices and effective and frequent feedback to ensure that you maintain clear and aligned expectations of each individual team member.

The People Behind the Project

Motivation and teamwork are essential for a successful project implementation. By understanding the psychology of motivation and the logistics of project management, companies and managers can create a supportive work environment that motivates employees to work effectively and efficiently to achieve more.

It is vital to remember that, despite the fast pace and incredible impact of technology, people have been and always will be at the center. It is paramount that companies and managers throw out the outdated practices of what motivated previous generations and continue to learn, grow, and purposefully apply psychological principles to be culturally and generationally informed leaders.

1. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.

2. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.

3. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.

4. Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. (2000). “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being”. American Psychologist. 55 (1): 68–78.

5, Ryan, R. M.; Deci, E. L. (2000). “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being”. American Psychologist. 55 (1): 68–78.

6. Vroom, V. (1964) Work and Motivation. Wiley and Sons, New York.

7. Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18 (1), 105-115. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1037/h0030644.

8. Janis, I. L. (1997). Groupthink. In R. P. Vecchio (Ed.), Leadership: Understanding the dynamics of power and influence in organizations (pp. 163–176). University of Notre Dame Press. (Reprinted from "Psychology Today," Nov 1971, pp. 43, 44, 46, 74–76).

9. Harkins, S. G. (1987). Social loafing and social facilitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23 (1), 1-18.

10. Harkins, S. G. (1987). Social loafing and social facilitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 23 (1), 1-18.