Screening is critical to reducing mortality: when detected early, the five-year relative survival rate between 2009 and 2015 was 92% for cervical cancer classified as localized, compared with 17% for cancers detected at the distant stage.1 Still, the American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates 13,800 new cervical cancer diagnoses and 4,290 cervical cancer deaths in 2020.2

At one time, cervical cancer was one of the most common causes of cancer deaths among U.S. individuals with a cervix; however, between 1955 and 1992, the incidence and death rates of U.S. cervical cancer declined by more than 60%. This decrease can be attributed largely to the development of the Papanicolaou test (Pap smear or Pap test)— one of the most effective cancer screening tests available.3

Claims and Litigation

Besides harming patients, undetected cervical cancer can result in expensive lawsuits, bad press, and regulatory scrutiny. In fact, failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis of cervical cancer are among the most prevalent medical malpractice claims encountered in obstetrics and gynecology; claims alleging a delay in cervical cancer diagnosis are difficult to defend.4 To avoid litigation and provide optimal patient care, it is important that cytology laboratory reports contain clear terminology, a proper interpretation of the Pap smear slide, a clearly stated recommendation by the laboratory, and a proper clinical follow-up by the ordering clinician.5

Areas of physician and laboratory negligence in cytology malpractice lawsuits can include the following:6,7

- Delayed or missed diagnosis of cervical cancer

- Failure or delay in ordering diagnostic tests

- Narrow diagnostic focus or failure to establish differential diagnosis

- Improper sampling/scraping or identification (failure to collect and/or find abnormal cells on a slide)

- Failure to address abnormal findings

- Incomplete patient history or failure to follow up with the patient

- Inadequate patient or family education regarding follow-up instructions

- Patient nonadherence with follow-up call or appointment

- Absence of a quality assurance program

Many cases arise when a false-negative result is found on review of a prior Pap smear from a patient in whom cervical cancer was recently diagnosed or when an unsatisfactory smear is not reported as such. These slides may be susceptible to being interpreted differently by various cytotechnologists and pathologists. Experts retained to review questioned slides in the context of litigation generally have the advantage of knowing that the patient subsequently developed cancer. Plaintiffs in these cases typically allege negligence against one or more pathologists or cytotechnologists, along with the director of the defendant laboratory and the primary care provider who obtained the Pap smear.8

Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening

Despite improvements in cervical cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment, care disparities still exist, and factors such as race, geographic location, and socioeconomic status can affect screening and treatment accessibility as well as mortality. According to the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “More Black and Hispanic women get HPV-associated cervical cancer than women of other races or ethnicities, possibly because of decreased access to screening tests or follow-up treatment.”9 In addition, the five-year overall survival rate for cervical cancer is 66%; however, the survival rate is 71% for white women and 58% for Black women and non-Hispanic Black women were 80% more likely to die from cervical cancer than non-Hispanic white women.10,11 Even greater disparities can exist among these populations

depending on the state and geographic area in which they reside and their socioeconomic status.12

Treatment disparities may also exist for transgender men. Such individuals are less likely to be current on cervical cancer screening than cisgender women, and may face challenges obtaining pelvic exams or Pap tests, as well as accessing culturally sensitive healthcare.13 Studies indicate that transgender men have higher rates of abnormal cervical cancer screening results, higher likelihood of not being screened for cervical cancer in their lifetime, and lower likelihood of receiving regular cervical cancer screening compared to cisgender women.14 Cervical cancer screening for transgender men should follow the same schedule as that for cisgender women.15

Educate Providers About Current Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines

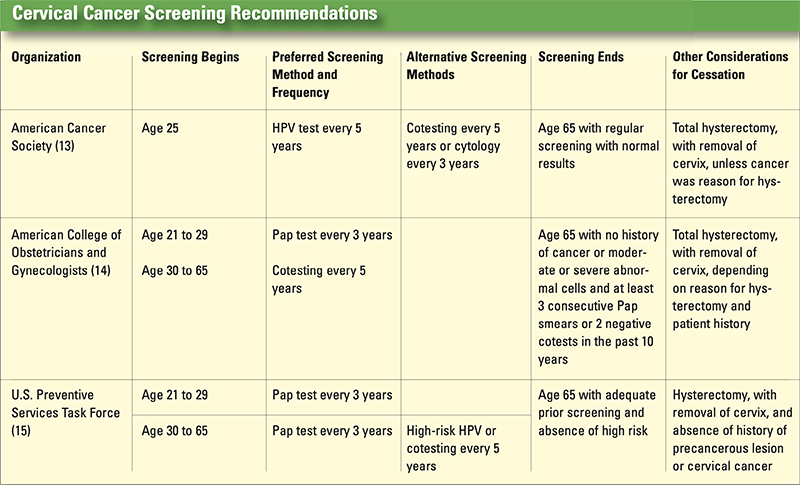

Professional organizations have modified and updated their guidelines regarding screening intervals, screening cessation, use technologies, and routine use of HPV testing as adjunct to cytology screening. Although cervical cancer screening guidelines have become more consistent,

healthcare providers must be ready to answer patients’ questions and clarify areas where there is no consensus (see Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations, p. 31).16

Based on a literature review and expert opinion, a panel of 13 experts developed interim guidance for using the HPV test as a primary screening method. The panel recommends that primary high-risk HPV screening can be considered an alternative method. Rescreening after a negative high-risk HPV screen should occur no sooner than every three years, and use of high-risk HPV as a primary screening tool should not begin before age 25.17

Educate Patients About the Importance of Cervical Cancer Screening

Affected patients should be educated about the importance of periodic cancer screening; however, patients should also be informed that the Pap test and the HPV test are not 100% accurate. Therefore, a yearly wellness visit should always be scheduled to ensure that the patient is in good health and to detect any warning signs of cervical cancer.

Patient resources from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and The American Cancer Society explain how testing is performed, the efficacy of the tests, and why it’s important to be screened for cervical cancer.

Review Laboratory Policies and Procedures

Mistakes that can expose the facility to litigation are often related to the patient profile, screening recommendations, management of abnormal Pap test/smear, documentation, communication, and follow-up.18

Patient profile. A complete patient history should be taken, and patients at high risk for cervical cancer should be identified and closely followed. Treatment of high-risk patients includes providing adequate HPV and HIV screening, timely Pap smears, yearly pelvic exams, and comprehensive patient education.19

Documentation of patients' clinical histories on laboratory requisition forms can expose primary care providers and laboratories to liability. The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) specify that requisition forms for laboratory tests must include:20

The patient’s name or unique identifier

The sex and age or date of birth of the patient

The test to be performed

The source of the specimen, when appropriate

The date and time of specimen collection

For Pap smears, the patient’s last menstrual period, and indication of whether the patient had a previous abnormal report, treatment, or biopsy

Any additional information relevant and necessary for a specific test to ensure accurate and timely testing and reporting of results, including interpretation, if applicable

Screening recommendations. Clinicians should adhere to recommended cytology guidelines, but these recommendations do not preclude the need for comprehensive yearly exams.21

Management of abnormal Pap test/smear. Clinicians should follow up with patients who have abnormal screening results. Such patients should be retested with the appropriate testing and follow-up regimen, as indicated by current guidelines.22

Documentation. Claims that might otherwise be defensible on the merits of the care provided can be made more difficult or impossible to defend when documentation is inadequate. Documentation should seek to “create a chronological word picture of the assessment, diagnosis,

treatment plans, and outcomes,” and should detail the following:23

Instructions to the patient (e.g., follow-up, further testing, referral to specialist) and clinical care decisions

Any telephone instructions provided

Signed consent forms that specify the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the diagnostic study or treatment

Informed consent conversations

Medical rationale supporting the clinician’s assessment, the diagnosis established or pending, and the treatment plan and subsequent alterations in conjunction with the patient’s clinical status

The patient’s understanding of the need for subsequent studies

Follow-up. It is important to follow up with patients about their cytology results, and follow-up appointments should be scheduled as necessary. According to ACOG, the following characteristics are important for any reminder system, whether electronic or paper based:24

- Policies and procedures. The tracking policy and procedure should be developed with input from the staff and should address documentation of follow-up, time frames for when to expect and relay test results, and processes for handling delayed or missing reports.

- HIPAA compliance. Whether by mail or electronically, all means of contacting patients should adhere to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, including limiting the amount of information disclosed via voice mail or to other individuals who may answer the call.

- Specificity. The reminder system should contain specific data and dates, including the dates for receipt of information and timelines for notifying the patient.

- Location. The reminder system should be centrally located in the office and should not be kept in individual patient charts. Reminders should be accessible to the entire staff.

- Reliability. Office staff should be cross-trained so that the system is reliable and efficient and does not rely on any one person. It should be updated and monitored regularly.

References

1. American Cancer Society. Survival rates for cervical cancer. 2020 Jan 3 [accessed

2020 Nov. 18]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/detectiondiagnosis-

staging/survival.html.

2. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for cervical cancer. 2020 Jul 30 [accessed

2020 Nov. 20]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/keystatistics.

html.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Genecologists. FAQs: cervical cancer

screening. 2017 Sep [accessed 2020 Nov. 18]. Available: https://www.acog.org/womens-

health/faqs/cervical-cancer-screening.

4. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

5. Perey Law Group PLLC. Cervical cancer and the misdiagnosed pap smear.

[accessed 2020 Nov 20]. Available: http://www.pereylaw.com/articles-videos/cervical-

cancer-and-the-misdiagnosed-pap-smear./

6. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

7. Perey Law Group PLLC. Cervical cancer and the misdiagnosed pap smear.

[accessed 2020 Nov 20]. Available: http://www.pereylaw.com/articles-videos/cervical-

cancer-and-the-misdiagnosed-pap-smear/.

8. Ibid.

9. Hamill SD. Washington Hospital reviewing hundreds of Pap tests after lawsuit.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2012 Nov 16 [accessed 2020 Nov 30]. Available:

https://www.post-gazette.com/news/health/2012/11/16/Washington-Hospitalreviewing-

hundreds-of-Pap-tests-after-lawsuit/stories/201211160187.

10. Lubin & Meyer PC. Misread PAP smear results in cervical cancer diagnosis

delay: $1 million settlement. 2011 [accessed 2020 Nov 30]. Available:

http://www.lubinandmeyer.com/cases/cervical-cancer.html.

11. Harrison J. Jury awards Minot couple nearly $10 million for misread Pap

smears. Bangor Daily News; 2015 May 15 [accessed 2020 Nov 30]. Available:

https://bangordailynews.com/2015/05/21/news/lewiston-auburn/jury-awardsminot-

couple-nearly-10-million-for-misread-pap-smears/.

12. Cattabiani M. Jury awards $10 million in cervical cancer diagnosis lawsuit. Ross

Feller Casey, LLP; 2015 May 20 [accessed 2020 Nov. 30]. Available: https://www.

rossfellercasey.com/news/jury-awards-10-million-in-cervical-cancer-diagnosislawsuit/.

13. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, Etzioni R, Flowers CR, Herzig A, Guerra

CE, Oeffinger KC, Shih YT, Walter LC, Kim JJ, Andrews KS, DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA,

Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Wender RC, Smith RA. Cervical cancer screening

for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer

Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Sep; 7095): 321-46. Also available: https://acsjournals.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21628.

14. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2019-

2021. 2019. Also available: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancerorg/

research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-africanamericans/

cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf.

15. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, Etzioni R, Flowers CR, Herzig A, Guerra

CE, Oeffinger KC, Shih YT, Walter LC, Kim JJ, Andrews KS, DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA,

Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Wender RC, Smith RA. Cervical cancer screening

for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer

Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Sep; 7095): 321-46. Also available: https://acsjournals.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21628.

16. American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer prevention and screening: financial

issues. 2020 Jul 30 [accessed 2020 Nov. 20]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/

cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/prevention-screening-financialissues.

html.

17. American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer prevention and screening: financial

issues. 2020 Jul 30 [accessed 2020 Nov. 20]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/

cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/prevention-screening-financialissues.

html.

18. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

19. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

20. American Cancer Society. The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention

and early detection of cervical cancer. 2020 Nov 17 [accessed 2020 Nov 30]

Available: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/

cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html.

21. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

22. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

23. The Doctors Company. Obstetrics and gynecology. A clinical guide to imporving

patient safety and managing risk. 2017. Also available: https://www.thedoctors.

com/siteassets/pdfs/risk-management/pdf-articles/10703_composite_singlepage_

fr.pdf.

24. Health Resurces and Services Administration. Cervical cancer screening clinical

quality measure. Available: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/quality/toolbox/

508pdfs/cervicalcancerscreening.pdf.